In the heart of Yellowstone National Park lies a deadly beauty: acidic, steaming pools that shimmer with color and quietly warn you to keep your distance. These are not places to soak. They’re cauldrons of geothermal heat, where temperatures can exceed 200°F (93°C) and the water is often more acid than vinegar.

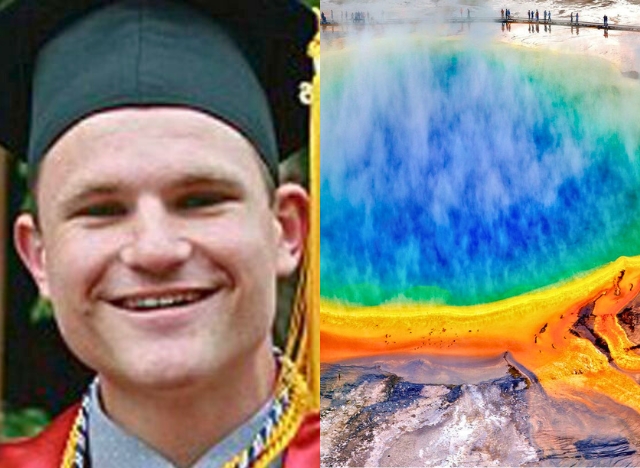

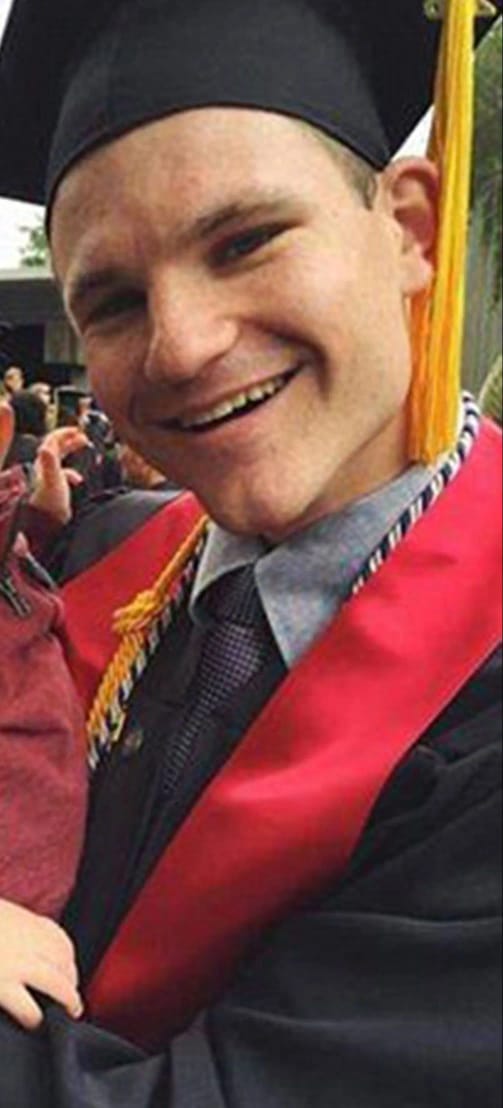

In 2016, a man named Colin Scott stepped off the boardwalk searching for a place to “hot pot” — Yellowstone slang for soaking in thermal water. He and his sister wandered into a restricted area near the Norris Geyser Basin. That’s where Colin accidentally slipped and fell into one of the pools.

Rangers responded quickly, but by the time they arrived, there was almost nothing left. His body had been dissolved by the superheated acidic water.

“There was a significant amount of dissolving,” said Deputy Chief Ranger Lorant Veress, describing the tragic recovery effort.

The pool’s temperature, combined with its corrosive properties, made it impossible to retrieve his remains. According to park spokesperson Charissa Reid,

“The water was very, very hot and acidic. We weren’t able to retrieve any remains.”

It’s easy to underestimate these pools. Their serene appearance — glassy surfaces, vibrant colors — can mislead even the cautious. But Yellowstone sits atop one of the world’s most active volcanic systems, and these springs are venting directly from the earth’s fiery core.

Every year, visitors are warned to stay on marked trails and boardwalks. Some ignore the rules and face consequences ranging from burns to death. Beneath the surface, this is not just water — it’s a chemical cocktail capable of erasing human presence in hours.

Yellowstone may be one of America’s most iconic parks, but it’s also one of the most dangerous. A place where the planet doesn’t just show its power — it lives it.